HELIX or CURVE OF CONSTANT SLOPE

| next curve | previous curve | 2D curves | 3D curves | surfaces | fractals | polyhedra |

HELIX or CURVE OF CONSTANT SLOPE

| From the Latin "helix", derived itself from the Greek

"eliks": spiral.

Other names: curve of equal slope, slope line, isocline curve. |

| The fixed plane being xOy, differential condition: | |

| i.e. in Cartesian coordinates: | |

|

Cartesian parametrization knowing the base of the helix, parametrized by |

|

| Radii of curvature and torsion, |

|

| Differential equation of the helices traced on the surface |

coming |

|

Cylindrical equation of the helices traced on the surface of revolution |

The helices are the curves the tangents of which form

a constant angle a with respect to a fixed plane

(P0), or a fixed direction d

(orthogonal to (P0)).

Therefore, the notion of helix in mathematics is more

connected to a mountain road with constant slope than to the helix of a

boat!

Concretely, we get a mathematical helix by cutting a

right triangle

out of a cardboard, placing it vertically on a plane and deforming it:

the hypothenuse takes the shape of a helix.

Necessary conditions for a curve to be a helix:

- curve for which the spherical

indicatrix of curvature is planar (therefore included in a circle).

- curve the principal normals of which remain parallel

to a fixed plane (equal to (P0)).

- curve the binormals of which form a constant

angle with respect to a fixed direction (the same as the tangents).

- curve for which the spherical

indicatrix of torsion is planar (therefore included in a circle).

- curve the torsion of which is proportional to

the curvature (Lancret theorem).

- trajectory of a movement for which the second,

third and fourth derivative vectors are coplanar.

- geodesic

of a cylinder (the cylinder generated by the lines parallel to

d)

- in other words, if we develop the cylinder on which the helix is traced,

the helix becomes a straight line.

A helix is entirely defined by its projection on (P0) (its base) and the angle a.

Examples (note that the helices are described by their

base or the surface on which they are traced):

- the straight line (lines on a surface

are therefore helices of this surface)

- the cylindrical

helix (base = circle)

- the conical

helix (traced on a vertical cone of revolution, base = logarithmic

spiral)

- the elliptic

helix (base = ellipse)

- the spherical

helix (traced on a sphere, base = epicycloid)

- the helix

of the paraboloid (base = involute of a circle).

- the helix

of the one-sheeted hyperboloid (traced on the one-sheeted hyperboloid)

- the striction

line of the milk carton

| - the catenary helix (base = catenary): it is traced on the hyperbolic cylinder Curve studied by Catalan in 1878. The catenary helix is the generatrix of the minimal helicoid. |

|

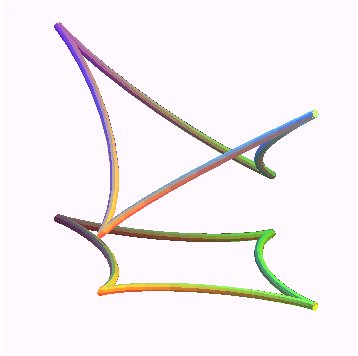

| - the torus helix (traced on

the torus, the reference

plane being orthogonal to the axis of the torus):

|

Torus helix with slope 1 |

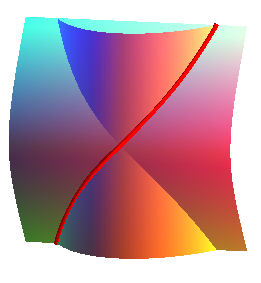

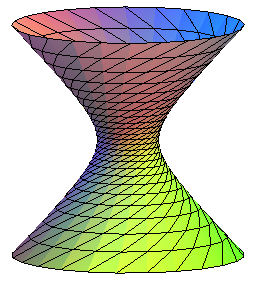

| Example of determination of the helices on a surface:

those of the hyperboloid

of revolution: x² + y² = z² +1, parametrized by

x = cosh u cos v, y = cosh u sin v, z = sinh u. Write dz/ds = tan a, i.e. dx² +dy² = dz²

cot² a, hence, here:

i.e. sqrt(cot²a - tanh² u) du = dv, from which we get v as a function of u. For a = pi/4 we get the included lines. The helices with cot a = 2 were traced opposite.

|

|

See also the surfaces

of equal slope.

| next curve | previous curve | 2D curves | 3D curves | surfaces | fractals | polyhedra |

© Robert FERRÉOL 2018